Trying To Place A Value On Memories

For 68 years I have saved a little red leather box.

That little box has survived each of our sixteen moves, and always found it’s way to a safe drawer where, surprisingly, I always knew where it was, but rarely opened it.

But not long ago, a friend mentioned that he was having an old pocket watch he owned restored, and that got me thinking about whether I should do the same thing to the two pocket watches in my little red box.

A Trip to the Jewelry Store

I laid the two pocket watches on the counter and matter-of-factly said to the watch expert, “I have these two pocket watches and wonder if it would be worthwhile to have them restored? What do you think?”

The expert turned the winding knobs, looked the watches over real good, and, with the true air of someone who knows what he is doing, said, “Well, it would cost you more to fix these up than they would be worth.”

“I wouldn’t mess with ‘em. Pocket watches like these are a “dime a dozen.”

Driving Home

Reality set in as I drove home from the jewelry store.

The more I thought about what the watch expert had said, and the more I thought more about my watches, the angrier I got.

A dime a dozen indeed! He didn’t really know anything about my watches, and somehow I had ignored what I knew about them too.

It was on that ride home that I began to realize how valuable my watches really are.

The Value of the Watches

If you guessed this from the very beginning, you were right.

The silver-colored (Silver) watch belonged to my grandfather, Edmon Odaffer (1865-1945), and the gold-colored watch (Gold) belonged to my father, Ray Odaffer(1900-1950).

I don’t know where my father and grandfather bought their watches, but I bet a dollar it was from the Sears-Roebuck catalog.

(Richard Sears started a company that sold pocket watches through mail order catalogs in 1888, and a few years later he and Alvah Roebuck, renamed their expanded watch company Sears, Roebuck & Company.)

But the real value of the watches is what they symbolize, and the memories they invoke in me. I’d like to take a moment to explain this.

My Grandfather Edmon and His Watch

Edmon was a successful farmer. He knew how to do it, and he taught his only son, my father Ray O’Daffer, to do it, too.

And he was very proud of “the home place” where he had moved and fixed up a good country house for his family to live in.

When it came time for him to quit farming and turn it over to my dad, Ed did what a lot of farmers dream about doing when they retire–he moved to town!

In town, Ed developed a ritual based on who he thought he was–an important successful, retired farmer who had made something of his life.

Every day, Monday through Friday, Ed would get up around 7 a.m. (awfully late, in the mind of an old farmer), and enlist my grandmother Mattie to help him get ready. She would bring him a freshly washed and ironed white shirt, a necktie, and his one and only good black suit.

Then Ed polished and wound his silver pocket watch, attached the watch fob, and carefully placed it his suit watch pocket.

Ed, with a reputation for being a little hyper and a quick mover, would twist his mustache several times, check his watch again, and take off.

Ed would walk several blocks to Main Street in Weldon, Ill., and take his place on a bench in front of the Post Office–where he stayed until time for dinner (12 noon, in those days).

Some others on the bench may have thought Ed was a little kooky, but it did not deter him. He was as regular in going there as his prized silver pocket watch was in giving the time.

As I look back on this, perhaps the silver pocket watch is a symbol of my grandpa Ed’s life. He was a man who made good use of his time on earth, always gave his family and grandkids the time of day, was always on time for appointments, and was proud of himself and what he did and the legacy he left for his descendants.

My Father Ray and His Watch

Ray, following in Ed’s footsteps was also a good farmer. He was also a school board member and sold seed corn for a while.

He liked his gold pocket watch and carried it in the watch pocket in his overalls.

I remember many time watching him take out the watch and check the time—whether it was in the field deciding when to come for dinner, determining when to stop running the trap line with me so he could get me to school on time, or checking to see if it was time to tune in the “Lone Ranger” for us to listen to on the battery radio.

Ray greatly enjoyed his family, and checked his prized watch to see if the plane was on time when he met his first granddaughter baby, who had flown in from California.

Like his father Ed, Ray bought a house in the country and moved it to town—remodeling it for he and my mother Ruby to live in when they retired. He was looking forward to a rewarding retirement.

Sadly, my father Ray would not be able to retire and use the house, because he was killed in a farm accident on March 23, 1950, when he was 49 years old.

He got caught in a post-hole digger that was attached to the back of our Allis Chalmers tractor and was crushed. A terrible life-changing accident—for all of us.

As usual, on the day of his accident, his gold pocket watch was in his pocket.

If you look at the watch carefully, you can see that the front plastic face cover is missing, and there is a small dent on the back—perhaps evidence that the accident took a toll on the watch too.

So, as I look back on it, the gold watch is the symbol of my father’s golden life for 50 years, and for all the time and help he gave to our family and to me when I was growing up. It also symbolizes the special times in which he really enjoyed his shortened life, like the trip to the airport.

The Moral of This Watch Story

Instead of being worth “a dime a dozen,” my watches, because of the memories they evoke, are very valuable and precious. I wouldn’t sell them for any amount of money.

So maybe we should stop taking our antiques to the “Antiques Road Show” to be evaluated.

Rather, we should take time to think hard about the memories they evoke, what they symbolize, and determine their true value ourselves.

A Notable Veteran: William Henry Gray

Every Veterans Day I think about my Uncle Bill Gray — William Henry Gray, to be exact. He was the first veteran I ever knew.

It’s not that Uncle Bill was my favorite uncle to whom I was deeply devoted.

But he did play a role in my life. I recall him playing Pinochle with my family and taking me fishing a couple of times. He also gave me an army belt, some army uniform buttons, and an army hat. And he showed sympathy, as best he could, when my father was killed in a farm accident.

But this year was different. I decided to tell Uncle Bill’s story, which I have never done before.

Not just because the official goal of Veterans Day is “to pay tribute to all American Veterans — living or dead…”

Or because his story is so much more interesting than any other veteran’s story.

Rather, I’m telling his story out of respect for Bill Gray, because his story is notable, and because it may have a message for us on this Veteran’s Day.

Bill Gray and World War I

Bill Gray was born in 1899, in Weldon, Illinois.

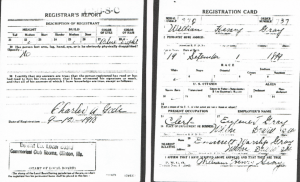

When he finished high school, World War I was heating up, and he registered for the draft. (Click on the draft registration cards below to enlarge.)

Without thinking twice, Bill quit his job in Uncle Gene Gray’s dry goods store, passed up an offer to work in a bank, left a fairly serious girlfriend, and enlisted in the Army.

After basic training, he was shipped to Europe, where he fought in the infantry in 1918, during the latter stages of the war. According to my mother (Bill’s sister), Bill fought in France, and later, in Belgium.

He came home after the war, and tried to get his 20-year old life back in order. His girlfriend had died in a flu epidemic while he was gone, and life must have seemed pretty empty.

My mother said that it wasn’t easy for him.

Bill somehow felt lost in society and didn’t feel appreciated. His friends and relatives would simply say that “Bill is generally on the grumpy side.” No one thought much about Post Traumatic Stress Disorder in those days, instead blaming any soldier’s problem on “shell shock” or “battle strain.”

But as years passed, Bill began to feel a little better, and life went on.

Bill Gray and World War II

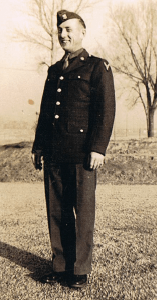

I was 7 years old when Pearl Harbor was bombed in 1941. Everyone in my broader family was worried when Bill announced that he was going back in the Army, to help, he said, “protect our countries four freedoms.”

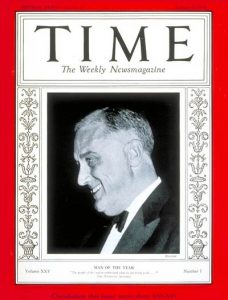

When an adult, I asked my mother why he would have said something like that, and she reminded me that Roosevelt had given his famous “Four Freedoms Speech” about 11 months before the Pearl Harbor attack, and Bill had listened to it on the radio.

Roosevelt proposed four fundamental freedoms that people everywhere in the world ought to enjoy: Freedom of Speech, Freedom of Worship, Freedom from Want, and Freedom from Fear. Norman Rockwell was commissioned to paint the pictures.

Once I heard that Bill had mentioned the four freedoms, I framed prints of them, and kept them on my wall. (Click on the prints below to clarify.)

So, on Sept 9, 1942, Bill re-entered the Army to serve in WWII. He was 43 years old, and he was in “for the duration of the war + 6 months”

It was a serious “re-up” if there ever was one, coming 24 years after his first enlistment in WWI. And he left behind a fairly serious girlfriend named Frieda Belle Cackley.

When he returned from the war in 1945, Bill tried to start where he left off. But to the surprise of just about everybody, including Frieda Belle, it did not work out, and they were never married. Two wars had took their toll on Bill’s love life, ruining relationships with perhaps the only two serious girlfriends Bill had ever had.

I tried to get Uncle Bill to talk about his experiences — how he felt about leaving a bank job and a serious girl friend to go to WWI, and leaving a potential wife to go to WWII, and how it felt to come back.

But he simply did not want to talk about it. So I still wondered if he had ever felt thanked, and appreciated.

But, in the spirit of Paul Harvey, there is “a rest of the story.”

The Rest of the Story

In 1994, eight years after Bill Gray died, my wife Harriet and I traveled to Europe with our friends Herm and Evelyn Harding, and stopped off in Belgium to visit the family of our AFS Student, Phillipe Bastenier,

After we’d been there a couple of days, Phillipe’s father, Jacques, decided to have a big party for us, and invited all of his relatives.

As the party progressed, a wizened old man who had been sitting alone in a chair, got up and made his way over to Herm and I. I believe he said his name was Peter.

He placed a hand on each of our arms, and in broken English said “You are the Americans. I want to thank both of you from the bottom of my heart for all the help the American soldiers gave us in the two wars. When the Germans were about to overrun us, the Americans were always there with food and military help. I feel so much gratitude, and have always wanted to thank someone.”

As he explained further and expressed his gratitude again, we all three had tears in our eyes.

When I went to bed that evening, I recalled that Uncle Bill fought in Belgium in WWI, and suddenly it hit me.

Bill Gray, that very evening, was finally getting his thanks, through me, for helping preserve American Freedoms, and for helping preserve Belgium’s freedoms as well!

And somehow, I could see him hearing the Belgium thank you, reacting initially with his war-induced grouchy demeanor, but secretly cherishing the thank you for the rest of eternity.

And now you know the rest of the story!

What We Can Learn From Bill Gray’s Story?

When I think of Uncle Bill’s story, three things come to mind.

First, we live in a country that enjoys freedoms, including the Four Freedoms Bill Gray thought about when he re-entered the Army in World War II. There are people in many nations who would die for these freedoms, and have. The United States of America, warts and all, is a great place to live and a place to cherish and protect.

Second, From the Revolutionary War until today, our veterans, in the spirit of Bill Gray, have sacrificed in many different ways to protect our country’s freedoms. They are men and women, who, to the person, have given a portion of their life, and did what the military asked them to do.

Third, there are 23.2 million veterans in the United States, 9.2 million of whom who are over 65. We need to genuinely thank them for the sacrifices they have made on our behalf, even if the thank you is “a message from Belgium!”

And we need to improve medical services, like those Uncle Bill may have needed and didn’t get, so all can function effectively in society.

President Harry Truman who, like Uncle Bill, fought in the infantry in Europe in WWI, said.

“Our debt to the heroic men and valiant women in the service of our country can never be repaid. They have earned our undying gratitude. America will never forget their sacrifices.”

And this goes for you too, Uncle Bill.

Another Slant On Living On A Farm

A wise friend recently said that every time a person tells about his or her experiences as a child, he or she subconsciously revises them just a little bit.

It just came to me that if I tell of my farm experiences maybe one more time, I might finally get the story right.

So, to give my descendants a better feel for “That’s The Way It Was,“ and to stimulate you to think about your childhood again, here is a “revised” thumbnail sketch of what I remember about living on the farm.

How My Farm Life Began

Old Doc Marvel came two miles from Weldon, Illinois to our farm house — in a snowstorm — to deliver me on Feb 3, 1934.

My mother was very pleased with her new baby, and announced that his name would be Phares Glyn—named after her mother Alice Phares.

Doc Marvel expressed immediate dislike for the name — mumbling that “Phares Glyn” sounded too much like “Paris Green” (a very poisonous bright green powder that was used as an insecticide and also as a paint pigment).

But my mother was unwavering, and that was that.

However, for some strange reason, she had a dislike for the color green throughout her life.

What Kind of World Was I Born Into?

If you would have questioned my mother about the world at that time, she might have said, “It is going to hell in a handbasket.”

After all, 1934 was one of the hottest years on record and arguably one of the worst years of the Great Depression.

And with John Dillinger and Bonnie and Clyde running around the country robbing banks and shooting at FBI agents, things looked grim indeed.

Internationally, too, things were in a mess — Hitler was staging a bloody purge of the Nazi party and declaring himself Fuhrer — and Japan was beginning to re-arm its warships as it renounced treaties with America.

But, although my mother probably didn’t know it, there was a lighter and more positive side.

For example, Franklin Roosevelt — because of his New Deal — was Time magazine’s Man of the Year.

And “It Happened One Night,” the first film to ever win the Oscar “grand slam” (Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Director, and Best Screenplay), directed by Frank Capra and starring Claudet Colbert and Clark Gable, was a hit in 1934.

And “It Happened One Night,” the first film to ever win the Oscar “grand slam” (Best Picture, Best Actor, Best Actress, Best Director, and Best Screenplay), directed by Frank Capra and starring Claudet Colbert and Clark Gable, was a hit in 1934.

So was a cartoon, “The Wise Little Hen”starring newcomer Donald Duck

Gable wore no T-shirt in parts of his film, so all the cool males stopped wearing them, too.

Donald Duck wore no pants in the cartoon, but didn’t have the same effect on the population.

Also in 1934, Mae West was in her prime. And Raquel Welch, Brigitte Bardot, and Pat Boone were born. When we were older, my wife Harriet and I admitted to each other that in our teenage years we were reasonably pleased that these three graced our presence.

And by the way, Ritz crackers were invented in 1934, cost 19¢ a box, and were all the rage.

But not for my family. If my mom and dad somehow had 19¢ to spend, they bought a couple of gallon of gasoline for our old McCormick 10-20 tractor.

What Was The Deal On the Farm?

I have a lot of fond memories about growing up on the farm, and remember that it was trying and a lot of work, but also some fun.

But as I look back on it now, I think we gave more time and attention than one might expect to having food, keeping warm, keeping clean, being clothed, disposing of our waste, and a few extras.

Having food

Our family, led by my mother, put hundreds of hours every year into making a garden and harvesting and preserving the vegetables it produced.

There were a lot of Ball fruit jars filled with everything from green beans to pickles in our underground root cellar after we had finished canning.

We also raised chickens, cows, and pigs, and believed they were on this earth to provide chicken, beef, and pork for us to eat.

Butchering steers and hogs was a yearly community event, and killing and preparing chicken to eat was a daily phenomenon to behold.

And finally, we milked several cows by hand to have plenty of milk to drink and cream to use in cooking.

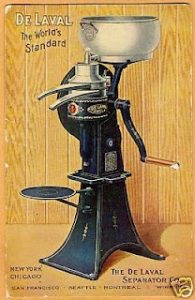

We even drummed up enough money to buy a used De Laval Separator, that put the milk out one spout and the cream out another.

Keeping Warm

We were pretty concerned about keeping warm in the winter on the farm.

One of my jobs when I got older was to carry cobs into the house every night in the winter to feed our cook stove. We used the cook stove to cook with and also to heat bricks to put in our down comforter when we slept upstairs.

We also carried in coal for the big living room stove. If we got too much coal in that stove the and the wind came up — as it often did in the winter — we tried to control the burning of the coal by trying to shut the flue off. Often we couldn’t do this and the stove would get red hot.

Many a time I was scared to death that the red hot stove would set the house on fire and burn it to the ground.

Keeping Clean

It was pretty hard to keep clean with no running water and no bathtub.

Trying to sit in a small round washing tub to take a bath was a big challenge, but we all tried to do it.

One of the greatest days ever was when my father found someone who was throwing away an old bathtub, with ornamental legs.

We couldn’t hook it up to running water, but we put it on the porch, and delighted in carrying water to pour in it so we could take what we thought was a real honest to goodness bath.

And, of course, we had to keep our clothes clean too. My mother used a washboard and a ringer to do all of the washing. She taught her daughters to do it, but it was unheard of in those days for a male to touch this “laundry equipment.”

To do the laundry, you put soapy water in the left tub, and rubbed the soapy clothes up and down on the washboard to get the dirt out. Then you ran the clothing through the ringer into the rinse tub on the right, followed by a foray into the back yard to hang all the washed clothes on a clothesline to dry.

Hooray for the modern washer and dryer!

Being Clothed

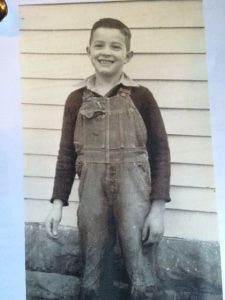

As I look back on our clothes situation, I feel that I spent my whole young life in overalls, as this photo of me attests.

And “dressing up” essentially meant taking a bath and changing into clean underwear and overalls.

As for my mother and sisters, they became excited when my dad bought a new sack of feed for our animals.

As you can see, the feed sacks had prints on them and this material was used to make dresses for the women in the family.

Disposing of Our Waste

I’m not sure why we didn’t get overwhelmed with germs on the farm in 1934, with such deplorable sanitary conditions.

We had an outdoor privy instead of an indoor toilet, so you can imagine the consequences.

We used chamber pots at night if we had to, and endured the olfactory agony of taking them out the next morning.

And it is true — we used the Sears Roebuck catalog as our toilet paper in the outdoor privy, overjoyed when it was at its newest and we could find the mail-order pages that were softer than the hard shiny ones.

We also used corn cobs when the going got rough and we ran out of paper, or visa versa.

A Few Extras

We had no telephone at first, but much later got on a party line. When you made a call, it was much like making a cell phone call today in a public place. All our neighbors could hear every word.

We had no electricity, so no lighting except small kerosene lamps.

Another great day was when my father found enough money to buy an Aladdin Lamp, which had a wick like a modern day camping lantern. It gave so much more light than a kerosene lamp that we thought we’d died and gone to heaven.

We also had a battery radio, but because we had little money to recharge or get new batteries, what we listened to was rationed.

The Saturday Night Barn Dance, The Lone Ranger, Lum and Abner, The Green Hornet, and Jack Benny — listened to by millions of people — were also our favorites, and were enjoyed by all.

What Was The Impact of All of This?

The Farm Community! Some problems, some healthy fears, some great joys, and a great place in which to grow up.

So in conclusion, here’s a picture of my dad, me as a potential farmer, and a poem I wrote that gives my final thoughts about the farm.

The Farm and Me

I liked living on a farm, with roosters, ducks, and goats.

And enjoyed slopping hogs and feeding horses oats.

I loved calling cows to come and had milking down pat.

The cows gave lots of milk for us, and plenty for the cat.

We planted the seeds and helped the new plants grow.

And we cut weeds from fields so none would ever show.

At harvest time we gathered grain to fill the larders up.

Satisfied with a job well done, we even praised the pup.

We took in the fresh air and relished most of the work.

Seeing animals meet a new day was yet another perk.

We provided all of our own food with no need for things.

I loved the basic simple life and the security it brings.

But not all was fun upon the farm I tell you for a fact.

As for cleaning barn stalls no one wanted in that act.

Cleaning chicken houses bared smells hard to believe.

With odor as the spreader spread too gross to conceive.

The privy and the potty both were awfully hard to take.

And bathing in a 3-foot tub would even thwart the snake.

Light from lowly kerosene, and warm from cobs and coal.

And bricks in bed to beat the freeze all really tried our soul.

Offing garden fires and snakes called for our every ploy.

And the dredge ditch with its Gypsies gave very little joy.

Shutting off the wild windmill was sure a first class pain.

And a ramming by the bull was like a bumping by the train.

We worked from dawn to dark the day was never done.

When hail or fire ruined crop or barn it wasn’t any fun.

Castrating hogs finally broke the pleasure camel’s back.

And rising at five o’clock was enough to make you pack.

So as I grew up learning and became full of farming lore.

Insight came to me once, and later appeared a lot more.

A farmer I was not going to be, come inferno or a flood.

It was plain as the nose on my face it wasn’t in my blood.

Things Are Not Always What They Seem

- At June 30, 2016

- By Phares O'Daffer

- In All Posts, Genealogy

1

1

What do you say when someone asks you what your ancestry is?

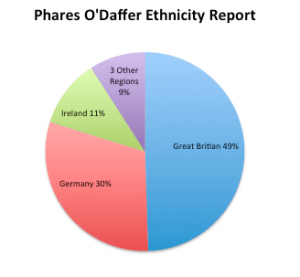

With me, it has never been a problem. “I’m German,” I always say with a big smile. “Kannst du sagen?”

I love it when someone asks, because everyone thinks that the last name “O’Daffer” has to be Irish—and I get to surprise them.

And, of course, I follow up by telling them that my name was originally “Odoerfer,” pretty obviously a German name.

“Somebody just poked an apostrophe in there to make it appear more classy,” I say.

Then, if they aren’t too glassy eyed already, I tell about my ancestor link to Germany, Johann Wolfgang Odoerfer, who was my great- great-great grandfather. He came to America as a Hessian soldier, and defected to fight with the Colonists in the Revolutionary War.

I also tell them, “He stayed in America to marry a Pennsylvania woman, and because of them, here am I.”

All of this sounds well and good, but, surprisingly–as I have recently found out—it is not an accurate picture of my true ancestry!

Taking The DNA Leap

About 8 weeks ago, I saw that you could get a DNA kit from Ancestry.com, spit in a vial, send it back, and after a while get an Ethnicity Report from them telling you what nationalities were in your DNA.

Since I like a bargain as much as anybody, and the reduced price was $79, I ordered the kit, and put the wheels in motion.

Sure enough, in about 5 weeks, my Ethnicity Report popped up on my Ancestry.com website, and you could have blown me over with a feather.

It’s All in The DNA

There it was. While my DNA showed a significant part of my ethnicity was German (30%), the major part was English/Scottish (49%)!

And, much to my pleasure, there was a little bit of Ireland in there too (11%).

So, lo and behold, and contrary to what I’ve been telling everyone, I am 70% non-German!

What I had failed to take into consideration in my “I’m German” past was that when you are born you get 50% of your DNA randomly from your father, and 50% of your DNA randomly from your mother.

So I must have gotten a pretty heavy portion of my mother’s British/Scottish DNA, and a lighter portion of my father’s German DNA.

I knew that while my great-great grandfather William Gray on my mothers side lived in Ballyjamesduff, in County Caven, Ireland before he came to America, “Gray” is not thought of as an Irish name.

Now I find out that the people named Gray came from the noble Boernician clans that lived in the Scottish-English border regions, and that many of these people later moved to Ireland.

If I had not been so hung up on the male side of my family, I might have came a little closer to my true ethnic origins, earlier in my life.

So What’s The Moral Of The Story?

Well, maybe the upshot of all of this is that determining the nationalities of your ancestors is a difficult process, and, if we aren’t careful, we can be easily fooled by our genealogy research.

Even determining one’s ethnicity from a DNA sample isn’t an exact science, and often involves an estimate based on the average of an analysis of a large number of samples of your DNA.

But if you want to get a little closer to your correct ethnicity, find out about others who have the same ancestral DNA as you, and have some fun along with it, shell out $79 (without discount, $99) to Ancestry.com, and send them some spit.

Some Thoughts About Civility

When I was quite small, my mother didn’t tell me about the importance of civility —she taught me. And the Church backed her up.

I can remember sitting on her lap and being subjected to example after example of what it meant to be a good person and treat people right.

And as I grew up—acutely aware of my shortcomings—I was still pleased when I heard a neighbor say, “He sure is a polite young boy.”

But I think I knew even then that there is much more to civility than politeness. And that seemed important to me.

But could I be making too much of this? Is it really all that important, or is it just the last vestige of a prudish, old-fashioned idea?

Here are some of my thoughts on the subject.

Just What is “Civility” Anyway?

How about, “Civility is treating all others with respect, as you would want to be treated.” *

Or maybe, “Incivility is intentionally using rude and thoughtless words and actions.” *

Or possibly, “Civility is claiming and caring for one’s own identity, needs and beliefs without degrading someone else’s in the process.”**

Or even if it we use the Merriam Webster dictionary definition of civility as “polite, reasonable, and respectful behavior,” I think we all get the picture.

It seems that civility has to do with the way people present themselves and the way they treat others.

In a sense, civility is a chosen way of operating that seems to feature our better selves– a deliberate interaction with life that choses to enrich rather than to degrade.

Some of My Experiences With Civility

In thinking about all of this, I searched for examples of civility that I had noticed as I was growing up.

For example, I grew up in a farming community near Weldon, Illinois. There was a lot of “listening in” on the local party telephone line, so everyone knew everyone else pretty well.

But when serious, personal things came up, the involved party just asked everyone to hang up and give them some privacy, and they did!

I thought this “unwritten telephone law of Weldon“ was an example of civility- polite, reasonable, and respectful behavior as it relates to the needs of others.

Another example was when I was around 7 years old. A neighbor girl about my same age, who didn’t always tell the truth, really got on my nerves. One day I called her a couple of bad names, and ended up with “Liar, liar, pants on fire.”

When she began to cry, I think my mother’s lessons on civility instantly took on a practical reality.

Even though “sticks and stones may break my bones, but names will never hurt me,” they had. I realized at that instant that it really was cruel, hurtful, and uncivil to harass people and call them bad names.

Another situation in Weldon when I was around 9 years old dramatically illustrated the force of civility in our community.

I was puzzled by the sudden fury of activity in and around Weldon.

Many men of the community, including the minister and other prominent citizens began having “secret” meetings.

And I couldn’t understand why they started wearing robes made out of white sheets at the meetings.

It seems that some African Americans (The Weldonians used the N word then) had come to our community, and the reaction had been to start a Klu Klux Klan group, with the intention of getting them to leave.

I overheard my mother and father in a heated discussion. My mother knew this was no way to treat human beings, and was not right.

The issue very quickly came to a head, and it was my 9 year old perception that it was my mother, together with some other women in the community who were instrumental in putting a stop to it.

After my parent’s argument, I didn’t see another white-sheet robe. They just seemed to have miraculously disappeared.

People in an otherwise civil community had gotten carried away, and it took the women to forcibly remind everyone that civility- treating others with respect, as you would want to be treated- was so much better than the alternative.

This next example still puzzles me today. Every Sunday afternoon in the town of Weldon, the kids got together for either a flag football game or a basketball game. Nothing unusual about that.

But what was unusual was that all kids who came (Age 8 or so on up), who might have been shooed away so the high school boys could get into a competitive game, were all welcomed and got to play!

To me, this was civility in action.

As an adult, I am blown away—when I think about it—with my parents, children, grandchildren, and relatives, and with the great number of my neighbors, church friends, golf buddies, and many other community friends and acquaintances who were or are, to the core, civil people.

But my experience is only part of the story.

Do We Have A Civility Problem?

A recent research study, Civility in America, 2013 (KRC Research, by Weber/Shandwick), stated, “Without a doubt, America has civility problems.” Here is some data. Of those surveyed:

- 70% believe a major civility problem in America has risen to crisis levels.

- 71% believe uncivil behavior is worse compared to a few years ago.

- 81% or those over 50 consider cursing uncivil. 68% of those younger than 50 feel the same.

- 83% believe that politics is becoming increasingly uncivil and that incivility in government is harming our country’s future.

- The average American encounters incivility around 17 times a week (via everyday situations like traffic, on social media, cellphones, online, in the classroom, in the workplace, on TV, etc.).

Why is Civility Important?

Back to my question in the first section, I think most would affirm that civility is not an old-fashioned, prudish, idea whose time has come and gone.

Quite to the contrary, it has a moral and lasting quality about it.

Civility, I believe, is the necessary glue that holds a home, a community, or a country together. It is a way of being that creates a climate of respect and concern for others.

Just imagine if we threw civility to the wind in our country. No army in the world can keep order in a country of people who aren’t orientated toward acting civility. We couldn’t enforce all the laws that would be broken. It would be chaos.

Even though it seems impossible to be 100% civil, I hope my examples from Weldon illustrate that when we are civil, the result is simply a much more satisfying life, resulting in an uplifted community.

What Can We Do About The Problem?

As they say about a lot of things that need to be done, “civility starts with me.”

So I guess we can start by being civil as much as we can, reaffirming civility whenever we see it, and finding our own way to stand against and discourage incivility whenever It rears it’s ugly head.

And so I’m off to Weldon, Illinois—back to my roots—to remind myself of what civility can do to make a welcoming, well functioning, and caring community- local, national, and world.

*Adapted from comments given in “Civility in America 2013”, a KRC research study by Weber Shandwick.

** Taken from the Institute for Civility in Government website

The “Great Debate”

On the evening of December 4, 2015, I found myself getting ready for a debate—an unlikely spot for an 81 year old who had never been in a formal debate before in his life.

As I waited to “go on stage,” My mind wandered to thoughts of Bernie Sanders and Maggie Smith.

Maggie is my age, and plays the elderly dowager on the popular TV show “Downton Abbey”—a rerun of which I had recently watched.

Bernie was now 74 years old, and I had heard him speak that very day as a candidate for President of the U.S.

He must know that, if elected, a 2nd term is a distinct possibility. And he would be my age, 81, before his second term would be over.

So these people — at my age — are or may be taking on some pretty serious tasks, involving thinking, memorizing and speaking. Why do/would they do it, when they could just be relaxing, and basking in their past successes?

That was exactly what I was thinking when Ann White, president of the College Alumni Club, asked me last year to participate in this debate with Wally Mead as a part of the club’s 125th anniversary celebration.

I asked then, “What would Maggie and Bernie do?” As I was about to step on stage, I was asking “Why would Maggie and Bernie do it?” (Recognizing, of course, that my little role was thousands of times less daunting than theirs.)

So is there a moral to this story — this microcosm of much more serious involvement? Let me paint a picture of the event and how I felt about it, to see if a moral pops out.

Why The Debate?

In the present day, the College Alumni Club members give speeches every month, followed by a discussion.

But in the 1890s, not only did they give speeches, they had debates!

So the Club wanted re-enact “an 1892 debate” in its 125-year Anniversary Celebration and Wally Mead and I got tabbed to lock debate horns with each other.

I guess they chose us “old guys” because the debate had actually taken place a long time ago.

What Was the Debate About?

Not only did they have Democrats and Republicans in the 1892 Presidential Election, but the new Populist party had slipped into the mix too.

And a part of the Populist platform was a position in favor of having a graduated income tax for the United States of America.

So the debate topic we chose was as follows:

Be it resolved that the United States should have a graduated income tax, rather than tax everyone the same.

Wally would argue the pro position, and I would argue the con.

What Were The Challenges in Preparing For The Debate?

Now Wally and I have been around the block a few times in our lives.

And we both knew that everyone involved would be better served if we used a script for the mini-debate, rather that have us two old competitive windbags hold forth extemporaneously.

And to further complicate the situation, the debate was to take up – stretching it quite a little – probably no more that 10-12 minutes of the evening’s program.

So, the first challenge was to create a viable debate script.

After carefully studying the mood and facts of the election of 1892, the key ideas of the graduated (progressive) income tax issue were identified, and a script began to take shape.

Early on, we decided that we needed a moderator for the debate. So we turned to a natural, Judge William Caisley.

And given that both Wally and I enjoy good humor, we decided to try to inject a little in the debate script.

Wally was a member of the Political Science Department at Illinois State University (ISU), so we dubbed him “Wadley Whistleblower.”

And since I was a member of the ISU Mathematics Department, my moniker was “Pervis Polynomial.”

And Bill Caisley was none other than “Judge Felix Fairshake.”

It wasn’t easy, but the script evolved, and became reality.

(Read the script to find out what we felt the important issues were.)

The second challenge was memorizing my script.

I felt it important to “know my part by heart” and I quickly found out that I simply didn’t memorize things as quickly now as I did when I was in high school plays. And I wasn’t nearly as confident that I wouldn’t forget it.

And here’s where I wished I could have talked with Maggie and Bernie.

The Debate Itself

The format of the debate was to have an introduction by the Moderator, an introductory argument by both the Affirmative and Negative, followed by a rebuttal statement by both the Affirmative and Negative, ending with a concluding statement by the Moderator.

Relying on Judy Brown’s well-stocked basement wardrobe, we acquired a hat, vest, and waistcoat from the 1890 era for Wadley and Pervis. Judge Fairshake wore a hat and one of his judicial robes.

And Wadley and Pervis both wore a “Spack-Stash,” an artificial mustache that Advocate Bro-Menn Medical Center had passed out at an ISU football game coached by mustached Brock Spack to commemorate male wellness month.

At the appointed time, we mustered up our best 1892 manner and the illustrious debate began!

Wadley and Pervis were not experienced debaters, but by all accounts they accomplished their purpose, and I think the audience was informed and entertained by it.

Check out this 13 minute video of the debate to see what transpired:

The Moral of the Story

Aesop said “Adventure is worthwhile.”

I considered doing this debate an adventure. As such, it wasn’t unlike other types of adventures.

It involved planning and work, facing unexpected situations, taking risks, occasional frustration, and it produced a surprising degree of fun and personal satisfaction.

And it was a learning and growth experience. It was worthwhile.

But I didn’t enter into the debate/adventure lightly. When first asked, my little squelcher demons leaped into action.

There was “inherited reticence,” dancing in my mind with “fondness for comfortableness.” And playing the music was “reluctance to do something new” accompanied by “can you really do it?”

And these devious squelchers might have won out if it hadn’t been that I sensed again the spirit of people like Maggie and Bernie.

So if there is a moral to this little story, it would involve extolling the virtue of forgetting how old you are, and jumping at the chance to put all your effort into doing something new to you.

If it makes a tremendous difference to society, all the better. But even if it doesn’t—take the leap and engage in an adventure you haven’t had before. It’ll do you good.

I may be naïve, but I don’t think the “Maggies and Bernies” of this world are doing what they are doing mostly for the money.

I think they do it because have learned the value of new adventure for their own well-being.

And, no doubt, they also want to make a difference.

Thanks to being captivated by the spirit of “Maggies and Bernies,” I had a great time with the debate. I think Wally did too.

The Cultivation of a Cubs Fan

By all reasonable standards, the Chicago Cubs have had a great year.

No, they didn’t get in the World Series. But with several very young players starting, they played with skill and class, and had some great wins that propelled them into the National League playoffs.

So as the thrill of this year wanes and Cubs fans look to next year, I find myself reminiscing about how I became a fan, and how it has lasted for all these years.

How It All Began

In the summer of 1941, with not even a dream about the following December 7th, I went to visit my friend Phil Whiteside, who lived a couple of miles down the road from our country house near Weldon, Illinois.

As a 7 year old, I had never been more than 50 miles away from my farm home, and was pretty green about the world.

I parked my bike, and was told Phil was in the living room.

To my amazed surprise, Phil was not only looking at a photo of a baseball team he called the Chicago Cubs, but, lo and behold, he was listening to them play baseball on the radio!

It was the first time I had ever heard the Cubs play, but by no means the last.

After listening to the game, Phil and I went out to his pasture with ball and bat, arranged dried up cow patties for bases and home plate, and played baseball to our hearts content.

He knew all the player’s names, so we pretended to be Bill Nickelson, Phil Cavarretta, Stan Hack, Peanuts Lowery, and a little guy, named Dom Dallessandro.

I liked Dellessandro and Cavarretta because they were left-handed– just like me.

Many years later, when the Cubs won their division title, I wrote Phil Whiteside a letter. I reminded Phil that I had followed the Cubs ever since that fateful day in 1941, and thanked him profusely for “introducing me to culture,” and for “broadening my worldview.”

In 1941, we had an old battery radio, which was basically only used to listen to the WLS Barn Dance on Saturday night, and possibly to Jack Armstrong and Lum and Abner during the week– if we did our chores.

Even though the battery wore down quickly, I convinced my Dad to let me listen to the Cubs, and a lifetime of being a Cubs fan began.

And How it Got Real Boost

The first time I went to a real Cubs game was when I was 14 years old.

The father and mother of another friend of mine-Terry Glynn– who were more worldly than my parents– invited me to go to Chicago with them and actually see a Cubs game.

I was beside myself with excitement, and it was really fun.

The only catch was that they three of them were all Cardinal fans, so I had to cheer for the Cubs on my own. And it was beginning to look pretty grim.

The Cardinals were ahead 3-1 with two outs in the bottom of the seventh, with Cubs Jeffcoat and Waitkus on base.

Then, as in a dream, Andy Pafko came up and hit a home run over the centerfield wall, putting the Cubs ahead to stay, 4-3. Click the link below to see the famous box score for that game.

60 years later, my son-in-law’s father, Chuck Thornquist, met Andy Pafko on a bus of retirees going to St.Louis, and Andy generously autographed his photo for me.

I always felt the autographed photo commemorated that great game in Chicago- my first real Cubs game– when Pafko hit the home run.

Needless to say, my first real game experience clinched it–And I have never waivered from being a Cubs fan!

How It Continues

Harriet and I attended many Cubs games over the years, laced with some very enjoyable side adventures. And we have watched a lot of enjoyable games on TV.

One great side adventure was the chance meeting and talk in Harry Carey’s restaurant in 2010 with Cubs manager Lou Pinella.

It was a great 80th birthday present for Chuck Thornquist– my son-in law-Bruce’s dad– who was having dinner with us.

Also in 2010, I was able to tour Wrigley Field with my son-in-law Bruce, Chuck Thornquist, and grandson Lee. We greatly enjoyed seeing the locker room, and the inner works of the centerfield scoreboard.

The highlight of my lifetime as a Cubs fan was being able to throw out the first pitch at a Cubs game in 2011. It was a wonderful adventure, and I felt like the Cubs pitcher of the year! (See the blog post on this website for the rest of this story.)

And finally, there was being at Wrigley Field for the exciting third win for the Cubs over the Cardinals on their way to the National League playoffs this year—in October 2015.

It was an electric atmosphere, with everyone waving a W(in) towel and standing up for practically every pitch. The Cubs hit 6 home runs in the game, and everything went the Cubs way.

Of course, the big goal is for the Cubs to win the World Series, which was not to be this year.

But as a Cubs fan for most of my 81 years, I can feel trends “in my bones,” and I’ve no doubt that the Cubs will be World Series Champs again– in my lifetime!

Go Cubs!

The Big Cubs First Pitch Experience

“Sold!” the Illinois Symphony fundraiser auctioneer shouted, and I realized I had just bought 4 box seat tickets to a Cubs game, and would throw out the first pitch.

No big deal, in the scheme of things. But Wow!

I’ve been a Cubs fan for 70 years, and have always wanted to throw out the first pitch at a Cubs game! So you can understand why I was pretty excited!

Getting Ready

I soon found that people generally feel that throwing out the first pitch at a Cubs game is a big deal. “Wow! How did you get to do that?!!!” “Boy, that’s the treat of a lifetime.” “We’ll be there!”

When 45 of my family and friends said they would come to the game, it was beginning to seem kind of important, if you know what I mean.

And then the trouble began. I hadn’t thrown a baseball in a couple of years, and it was shocking what age had done to my arm and my ability to throw a strike from 60 ft 6 inches.

It was harder to release the ball correctly. Hold it too long and you bounce it – let go too soon and it flies high!

“This shouldn’t be happening,” I thought. “I came within a sprained ankle of making the 1951 Illinois State University baseball team.”

“Well, not something that can’t be fixed with arm strengthening and practice,” I allowed, and began to do just that.

Tim Jankovich, the ISU basketball coach with Cubs first pitch experience, didn’t help.

He just had to mention the 14 inch high mound that throws you off, trouble finding the right release point when you’re tight and haven’t warmed up, and the effect of being in front of 40,000 people.

Then my neighbor said he had choked throwing a White Sox first pitch, and bounced it past the catcher to the backstop.

And Hal Lanier, ex-major league player and manager who was managing our local Cornbelters baseball team, said “Throw it from out in front of the mound.” When I rebelled at that, he retorted, with a hint of age prejudice in his eye, “Then throw it high.”

I realized that I needed to do a whale of a lot of positive imaging if I was going to throw a decent pitch.

The Big Day

The big day had finally arrived! After eating breakfast off of special menu entitled “Phares O’Daffer First Pitch Breakfast Menu,” I thought my family had planned a pretty great way to start the day.

Inside Wrigley field, my grandson Henry had made a sign, which read “My grandpa only pitches strikes!” I’m not sure that was what I needed right then, but I appreciated the sentiment behind it.

It was time. Harriet gave me an encouraging word, and I walked confidently through the crowd to the Cubs on-deck circle, with my bright Cubs shirt and hat, and my white shorts.

As I walked with my daughter Sue and son Eric–tossing my ball in my glove– toward the correct aisle, we heard a nearby person a few rows above the walkway ask, “Who is that guy??” I was beginning to wonder that myself.

There were three other people that day throwing out the “first pitch–” two women and a football player for the Indianapolis Colts. The two women were first, and I was relieved when they both bounced the ball to the catcher.

Here it Comes!

As the announcer said, “Phares O’Daffer will throw out the first pitch” over theloudspeaker, I walked confidently to the mound, pounding the new ball they had given me in my glove. I could hear my wife, kids, kids spouses, grand children, and friends cheering, and I saw our daughter Sara doing the video.

On the mound I got into the stretch position, and motioned to the catcher – the Cubs rookie Tony Campana. I was ready to pitch.

Maybe it was the positive imagining, but as I walked out onto the field to the mound, I felt pretty relaxed. I wasn’t nervous, but I was in sort of in a state of enjoying the moment and just doing it.

Raising one leg, I threw that pitch right toward the catcher (or so I thought).

OK, it was a little to the right of the catcher, and as the crowd said “oooh” he did have to make a quick move right and high to catch it.

But it went there on the fly, with pretty good velocity for a senior citizen, and he did catch it.

No bouncing the ball in, like a Cubs first pitch Ronald Reagan made when he was President. He requested, and got, a second try. At least I didn’t have to do that. And I did pitch from the mound.

It would have been a nice gesture if the football player had thrown his high and wide, but he proceeded to pitch a perfect strike.

But given the response I received from all my family and friends, you would have thought my pitch had been a perfect strike too. And maybe, symbolically, it was.

Basking in The Glory

As I walked back to my seat, not one, but two women asked me for an autograph! The first said, “ You must be somebody important to throw out the first pitch! Would you autograph my daughter’s baseball?” I think I had a very big smile when I wrote “Ike “Lefty” O’Daffer” on her ball.

I think the second lady simply was nuts over autographs. She would probably have asked one of the Peanut Vendors, should he have wandered by.

Also, as I walked back, several people said “nice pitch!” I checked each one to see if they wore glasses.

Later, in the 10th inning, with Campana on second and the bases loaded, Jeff Baker hit a single over third base and won the game for the Cubs.

I like to think that the Cubs “starting pitcher,” Lefty What’s His Name, brought them good luck.

Phares O’Daffer, aka Ike “Lefty” O’Daffer July 24, 2011

Extolling The Value Of Mischief

I could get into real trouble with all of the conscientious young parents I know by espousing the idea that mischief among the young contributes greatly to their healthy growth.

But I can think of nothing worse for a young boy or girl than a childhood or teenage life without at least a pinch of mischief.

And how stilted would an adult would be who had never freed himself or herself up for a spoonful of mischief?

I think the occasional mischievous twinkle in the eye is the hallmark of a well-adjusted individual.

If the ability to be a little mischievous from time to time isn’t just genetically there, or allowed in childhood, it probably isn’t going to ever happen later.

And that would be a pity.

It Depends on How You Define Mischief

Before getting any deeper into trouble with you parents who have enough trouble as it is, let me assert that I‘m not talking about really destructive mischief, or just plain meanness, excused as mischief.

Rather, I’m referring to what I call “good natured” or “wholesome” mischief.”

I will admit, though, that the line between good natured mischief and destructive, mean mischief often gets a little blurred- making it just a little risky to embrace mischief at all.

But I think the risk is worth taking. So let’s look some examples.

Example A, starring “Spray Fiddle”

My friend, Hobart Sailor, was a preacher’s kid, and a master of mischief.

Everyone called him “Fiddle,” but no one seemed to know why.

At any rate, I remember one of my first introductions to Fiddle’s brand of mischief.

We were sitting in church one Sunday, behind one of the stalwart ladies of the congregation. I think her name was Lillie.

The setting was rather peaceful. Fiddle’s father Dwight was in the middle of a long sermon, and we were getting bored, if not nearly asphyxiated by Lillie’s greatly over-applied perfume.

All of a sudden, I thought I saw a very fine stream of water emanate from Fiddle’s mouth and arch over the pew onto Lillie’s hat.

Upon questioning, my buddy I was now calling “Spray Fiddle,” whispered to inform me that if you moved your jaw right, you could spray!

I was amazed at this revelation, and decided to experiment. Lo and behold, I could spray too!

I was in a “thine is not to reason why “ mentality, and only later learned that there is an opening into a saliva gland inside the cheek, and that the proper motion of the jaw would activate it.

Fiddle and I proceeded to spray Lillie’s hat, but occasionally missed and got a little of Lillie.

I would guess that Lillie carried the mystery of the “rain in church” on that Sunday to her deathbed, or alternatively, may have interpreted it as “an act of God” commemorating her Baptism by immersion.

Example B, Starring “Sandwich Act Fiddle”

“Sandwich Act Fiddle,” as I called him on occasion, was also the cause of the only time I was ever kicked out of a class in high school.

He had found a very old ham and cheese sandwich in his locker that smelled to high heaven, and brought it to Chorus class, which met from two to three o’clock in the afternoon.

As Fiddle brought out the sandwich in the middle of our singing of “Go Down Moses,” and began his antics in reaction to the smell and his pretense to eat it, I found it extremely funny and became uncontrollably tickled. Of course, Fiddle kept a straight face.

As the sandwich found itself in odd places doing odd things, I was somewhat overwhelmed with the humor of it all.

Miss Harmony (name changed to protect the innocent) forthwith asked me to leave and go to the principal’s office.

I met our very stern, no-nonsense principal, Ernest Dickey, on the stairway leading to his office, and he asked me why I wasn’t in chorus.

I told him all the smelly details, and, without a reprimand, he told me to go sit in his office until the period was over, and then go to my next class.

Lucky for me, Mr. Dickey had been my Sunday school teacher for several years, and was convinced that I was a “fine young man,” not in need of dramatic punishment. Ah, the value of “connections.”

But there was no doubt that Sandwich Act Fiddle was the master of mischief.

The Gift of Mischief

From short sheeting and putting hands in warm water at Boy Scout Camp, calling to ask the local grocer if he has “Prince Albert in a can,” to making up weird names for teachers and animal names for friends, kids in Weldon were moved by the spirit of their friend, Mischievous Fiddle.

And many of us–even today–when contributing or appreciating a pun, making a funny remark, engaging in a practical joke, or becoming involved in any mild form of mischief that shines up our otherwise dull day–subconsciously thank Fiddle for his delightful gift of mischief.

Conclusion

Mischievous Fiddle- who enjoyed a long and stellar career as a Methodist Minister and District Superintendent in Michigan- has now passed away.

But his spirit of mischief lives on, and I know he would agree with me in believing that mischief, often accompanied by that certain twinkle in the eye, sort of flushes the stagnation from the soul, and seems to go hand in hand with a more creative approach to life.

It is the seasoning that needs to be sprinkled on the personality, and it is the therapy that puts things in perspective.

So please don’t underestimate the value of mischief in making life interesting and keeping you well adjusted– at any age!

The Importance of Healthy Marriages Through the Generations

We are in the season of Mothers Day and Fathers Day, so I find myself thinking about marriage and the family.

In a recent book (On God’s Side…) by Evangelical Christian author Jim Wallis, I saw the following statement.

“Stable Marriages are at the core of healthy households, and they are critically important for good parenting… without a critical mass of healthy and functional marriages, a society steers into real trouble.”

Wow! So everyone in my genealogy database who was married and had children could have contributed to that critical mass of healthy and functional marriages–a necessary condition for keeping “our society out of real trouble!” Pretty heady stuff.

But I wonder how those who were good marriage partners learned how.

Musings About How People Learn(Or Don’t Learn)To Be A Good Spouse

There were certainly no courses in my elementary or high schools about how to be a good marriage partner.

And, unlike the “birds and bees” sex education discussions that parents are supposed to try to have with their children, no one ever set me down and talked to me about how to be a good husband.

Neither my Sunday school teachers nor the minister who married us gave me any inkling about how I could be a good spouse.

I guess I was rescued just a little bit by a good Marriage and the Family Living course I took as a college student, and a book I read by Dr. Spock (he really wasn’t that bad).

But generally, it seemed that I had to learn by example, or just by doing—obviously not very systematic instruction geared for success.

So How Can A Person Be Helped To Become A Good Spouse?

I know “just telling” is not the most effective teaching method, but if I could go back in time to talk to all the young married couples in my genealogical data base, I would at least start by giving them a copy of the “Ten Love Habits of Highly Effective Spouses,” shown below.

I compiled/created this when my son Eric and daughter-in-law-to-be Stacy were planning their wedding in 1994, and have given copies of it to my children, and to several other young couples since then.

It doesn’t seem like much, but if you continue to think about it over the years—and even take it seriously– you might conclude that “Hey, there’s something important here after all.”

*******************************************************

Ten Love Habits of Highly Effective Spouses

RESPECT

Love is creating an “us” by nurturing each “me” – with guidance from “Thou.”

ACCEPTANCE

Love is accepting each other, rather than expecting to make an imperfect person perfect.

SUPPORT

Love is looking for the best in each other and what they do, and putting it into words.

COMMUNICATION

Love is patient listening, talking, and planning in a true partnership.

GENEROSITY

Love is letting it sometimes be 40-60 rather than insisting on 50-50.

HUMOR

Love is laughing- especially at ourselves- and having fun together.

CONSIDERATION

Love is doing and saying things that make each other feel good, rather than feel irritated.

PRIORITIES

Love is focusing more on the kind of you living in a house than on the kind of house you live in.

FRIENDSHIP

Love is being a best friend, knowing that true friendship is a union of two good forgivers.

GROWTH

Love is agreeing to work toward positive marriage habits, knowing that it is natural to falter.

Created/Adapted by Phares O’Daffer, May 28, 1994

**********************************************************************

The Bottom Line

Maybe it’s worth continuing to say things like this (or one’s own personal version) to our kids and grandkids, in the hope that it will become meaningful to them, or spark meaningful thoughts, and they will pass it on to their kids and grandkids, and so on.

If we can do even a little thing to maybe “help keep society out of real trouble,” it’s probably worth it.